List of historic properties in Agua Caliente, Arizona

This is a list which includes a photographic gallery, of some of the remaining ruins of historic significance in Agua Caliente, a ghost town in Arizona. Agua Caliente was once a small town in southern Maricopa County, Arizona. The small town evolved around the establishment of the Agua Caliente Resort. Also, included in the gallery is the Agua Caliente Pioneer Cemetery.

Brief history

Before the arrival of the European settlers in the region the area was home to the Tonto Apache tribe. They were the first to enjoy the natural hot spring waters which flowed in the area. Around 1748 and 1750, the Spanish missionaries arrived in the area and called it Agua Caliente which is Spanish for "hot water". Arizona belonged to Mexico until the end of the Mexican–American War in 1848. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo and the 1853 Gadsden Purchase clearly defined the U.S–Mexican boundaries.[1][2][3]

In 1858, a stagecoach station of the Butterfield Overland Mail was established in the "Flap-Jack Ranch". It was located six miles from the Agua Caliente hot springs along the Gila River, 84 miles from Fort Yuma.[2][3][4]

King S. Woolsey, an American pioneer rancher, Indian-fighter, prospector and politician in 19th century Arizona owned a ranch where the hot spring waters were located. On one occasion John Ross Browne and Charles Debrille Poston a.k.a. "Father of Arizona", due to his efforts lobbying for creation of the territory, visited and stayed in Woolsey's ranch. According to John Ross Browne: "We had a glorious bath in the springs next morning." By 1873, word had spread about the hot springs and many visitors, which included miners and cowboys went there.[2][3][5]

In 1897, a 22-room resort was built where Woolsey once had his ranch. It was named the "Agua Caliente Hotel". Arizona's first elected governor George W. P. Hunt was among those who visited and stayed in the hotel in the late 1800s. Various stone houses were built in the area, which included a store, saloon and residences. Plus, the small town also had a cemetery.[2][3][1]

Decline of Agua Caliente

The over-irrigation of the farms and ranches nearby may have been one of the causes for which the water of the springs dried up. During World War II, a swimming pool was built for the use of the officers of nearby Camp Horn. However, once the war was over and the Arizona State Highways 85 and I-8 were built and bypassed Agua Caliente, the town was deserted and eventually became a ghost town.[2][3][1]

Historic structures and artifacts

The following are the images of the Agua Caliente Resort and some of the ruins in Agua Caliente.

-

The Agua Caliente Resort.

The Agua Caliente Resort. -

Agua Caliente Resort pump house

Agua Caliente Resort pump house -

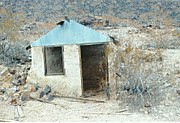

An Agua Caliente shack

An Agua Caliente shack -

Inside the Agua Caliente shack

Inside the Agua Caliente shack -

Stone house ruins

Stone house ruins -

Stone house ruins

Stone house ruins -

Stone house ruins

Stone house ruins -

Agua Caliente Pioneer Cemetery

Agua Caliente Pioneer Cemetery -

Lone grave in Agua Caliente

Lone grave in Agua Caliente -

Equipment used in the Agua Caliente Resort

Equipment used in the Agua Caliente Resort

Further reading

- Ghost Towns and Historical Haunts in Arizona; Publisher: Golden West Publishers; ASIN B003HF06YA.

See also

- Agua Caliente, Arizona

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Arizona

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Maricopa County, Arizona

References

- ^ a b c Ghost Town

- ^ a b c d e Ghost Towns of Arizona

- ^ a b c d e Block, Kathy (January 20, 2009). "Agua Caliente Cemetery". American Pioneer & Cemetery Research Project. Neal Du Shane.

- ^ The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Chapter LXII. Operations on the Pacific Coast. January 1, 1861 – June 30, 1865. Part I, Correspondence. pp. 1017–18, 1056 Distances from Los Angeles, Cal., eastward:

- ^ Thomas Edwin Farish, History of Arizona. Volume VIII, Phoenix, Arizona, 1918, p. 204